Designing for Water Quality

When you talk to people about greywater, they generally think very locally and in terms of their own benefit: free water for irrigation and how they can use it. But greywater use is actually part of a larger approach to managing water quality and treatment for a larger area.

Regional sewage treatment is done on everything that comes through the sanitary sewer lines (storm sewers drain directly, untreated, into local waterways, so do NOT dump things like kitty litter or dead raccoons down there, no matter how convenient you find the nice little hole in the street that you never have to take care of). The thing is, sometimes people do the wrong thing, like tie a gutter system into the sanitary sewer. This is illegal in most places and incredibly stupid everywhere, but people do it. That means that when it rains, the sewage treatment plants get overloaded with inflow, and they have to make untreated or insufficiently treated sewage discharges. This leads to toxic algae blooms and high bacterial levels in water, and all kinds of other bad stuff that nobody wants to think about.

Even on a regular, everyday basis, sometimes things get overloaded at the sewage treatment plant, and they have to make one of these discharges. It's how things go in crowded urban places, and it happens more often as places get more dense.

One way to reduce that load is to reduce the stuff you send through the sanitary sewer to the minimum: blackwater (in California this is water from toilets and kitchen sinks) and a little bit of greywater to help keep the pipes clear.

The other non-personal benefit of local greywater disposal is the recharge of aquifers, which helps local trees survive drought. Not only does drought tend to draw down the aquifer, but when people stop watering en masse as we have in the Bay Area, the regular recharge that happens from that watering also goes away. Greywater gives you back a trickle recharge of the groundwater and can help big trees weather a drought. And since greywater has nutrients in it, it actually helps the soil more than treated drinking water does.

We've wanted to do greywater for a while, but California first prohibited it, then had some terrible rules about it until the last code cycle, so until now we've had to just hope and wait. Well, with this big renovation we decided to go for it and add greywater handling to the project.

This is going to be one long post about our design and why I made some decisions about how to do it. I thought about breaking it up but you're already suffering through a multi-week rant about kitchen design so I couldn't do that to you.

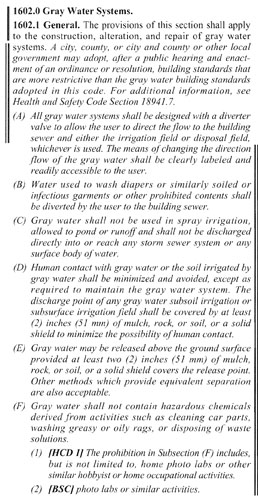

There are some rules that are always true of greywater systems:

A) You need a diverter valve because all of these systems must be designed so they can be turned off and all flow directed to the sanitary sewer. There are any number of reasons why that may be required but one big one is that there may be some kind of health reason why all used water in the city needs to be treated. It's also possible that the state could outlaw greywater again, and that would apply to existing systems as well. Remember to vote, everybody.

Diverter valves can be local to each fixture, or they can be located in a more convenient part of the house. You may have to crawl under the house to activate a diverter in a more remote location, or you can use a remote switch you've installed. The codes seem to be agnostic on this, as long as you can in theory change the flow of water at any time. We are going to use electronically controlled diverters with switches in each bathroom.

B) No poop in the garden. This is kind of a no-brainer. Human poop is a nasty thing and we spread enough of it around already through poor handwashing skills.

C) & D) They really do not want there to be ways to come in contact with the greywater, or for it to aerosolize. You may ask why, but consider that bathwater actually contains feces, too. Just send it underground as soon as possible, OK?

E) They do allow you to let it come out of a pipe and fall to the ground onto a mulch bed, which is pretty good. That way you can regularly inspect the pipe and make sure it's clear, and it makes it easy to find that ring you dropped down the bath drain, if you are one of those people.

F) If you need this note, you should not install a greywater system.

OK, so that said, what are our options?

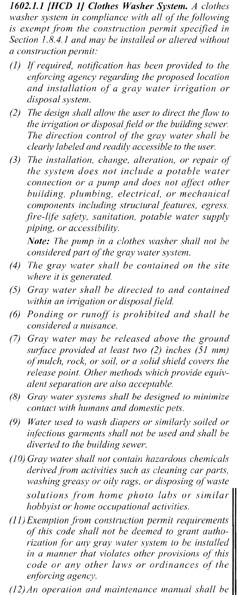

The first system, a simple laundry-to-garden greywater system, is now completely legal and does not even require a permit. Sweet! There are some restrictions but they are actually not that onerous, and mostly make plenty of sense. They're much the same as the general ones (anything that is repeated in the code, by the way, is something you should pay a lot of attention to):

Basically: contain the water, don't put hazardous chemicals or raw feces in your garden, and keep it simple.

About 90 percent of the plumbing code goes on the very simple idea that human contact with poop is a bad thing.

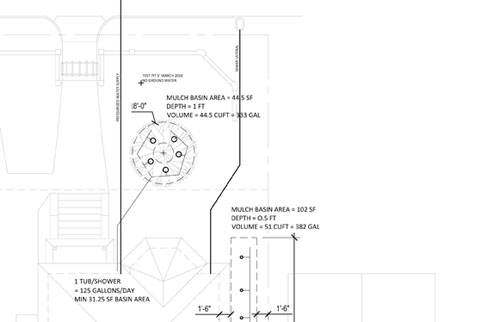

There are two other kinds of systems, for everything but the laundry. There are Simple Systems:

And complex systems, which I am not going to talk about.

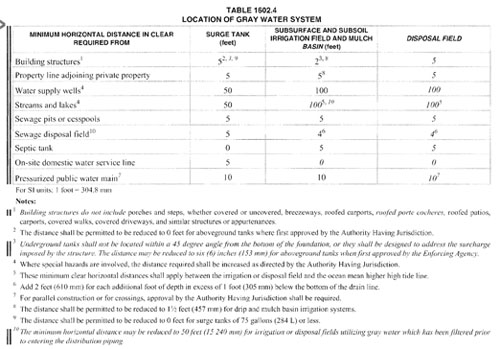

Simple systems handle less water, and you can make your system simple by breaking it up into several smaller systems, as we have done. In general a simple system will not have pumps, storage tanks (greywater cannot be stored at all for more than 24 hours), or filters, and if you have a system that has those features you may find your local building department will treat it as a complex system.

I'm not going to talk about complex systems because I am not a plumber, and if you have needs that require that kind of system you're going to need very specific design help that you would be very poorly served to get from a post on the internet. If you are dealing with a slope or a difficult site and need pumps or surge tanks or sub-grade drip or filtration, you should find a greywater design/build company and have them do this for you.

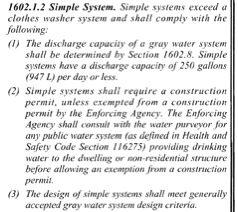

Our system is going to be a simple system, as simple as it can get. We will have gravity-fed pipes that run down and out into the garden for a relatively short distance, then fill a mulch basin through special mulch shield basins (basically irrigation valve covers repurposed). It's a slightly more sophisticated version of the kind of drains you see in many rural off-grid areas.

This is some of our site plan, showing the drain from the front bathtub. You have the choice of bringing all your greywater together and sending it out to the garden in one flow, but for the size of our house and the configuration of our garden, that didn't make much sense. So the drain from the new front tub goes out to the magnolia tree, the drain from the new back bathroom goes into the Fern Walk (which should have the chance to become more ferny with regular irrigation), the washer drains to the Passiflora vine, and the mop sink/dog rinse sink at the back of the house drains to a new bed where I'm going to plant bananas because I have almost no self control around new trees.

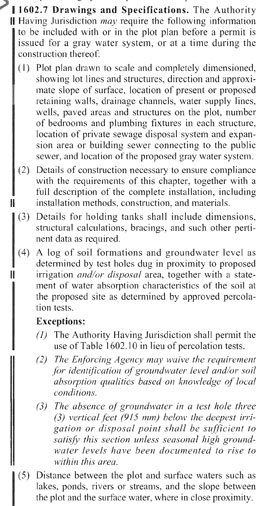

The code requires a site plan:

Which we already pretty much had together for the building permit drawings. We also had records of test digs (we dig a LOT of holes in our yard) and exact levels of seasonal groundwater starting back in 2005.

The need for knowledge of the level of seasonal groundwater was why I decided to keep all the greywater close to the house, where I know exactly how high groundwater can get even in the winter (because we keep it pumped down to 6 feet below the ground surface all year round).

I used Table 1602.10 for percolation, because every perc test I've done has exceeded the numbers in that table, so I went conservative:

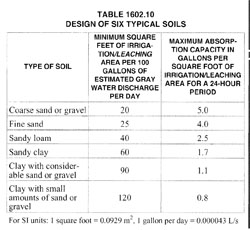

The place where you might get a little excited is here:

The code mandated discharge rates for each area fixture. Holy cow, they are high.

Right now, our water use is about 30 gallons of water a day. According to this table, the water discharge from non-toilet and non-kitchen sink fixtures that we have to design for is:

4 bedrooms = 5 occupants

3 showers or tubs = 3 x 25 x 5 = 375 gallons per day

4 lavatories = 4 x 25 x 5 = 500 gallons per day

2 laundries (we're putting an unused stub laundry in the basement in case the upstairs one is too disruptive for my parents) = 2 x 15 x 5 = 150 gallons per day

So the state insists that we design our greywater system to handle 1025 gallons of water a day, or 34 times as much water as we use in total, and that total includes toilets.

I made the decision not to include lavatories (sinks for the common folk) in the greywater system, so we can cut 500 gallons per day out of that number. Still. Holy cow. I got a litle excited about how much more water I would have until our actual water use numbers made it pretty clear that this will be a minimal amount of water on the busiest of days.

So use these numbers to design your system, but don't get too excited about how much water you will have.

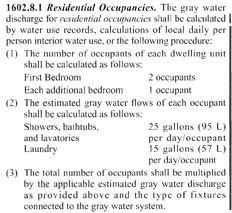

The other thing you need to know what designing is about the mandatory setbacks. There's Table 1602.4 that details all the setbacks for various kinds of systems.

(I know you can't read that, but the whole chapter is available online for free here. And in other formats elseweb.)

Basically, you get a bonus reduced setback if your system is not pressurized or handles a lesser amount of water.

The one thing that people like us in a high-groundwater city have to consider is the groundwater height restriction:

That's not nothing, but in general even in places like Alameda the actual groundwater is well below the ground surface in most seasons of the year. If there's any question, you can hire a geotechnical engineer to come out and do a soil report with percolation tests and location of groundwater in the places where you want to do greywater for a couple of thousand dollars. Is that expensive? Yes. But you'll get less fight from your city if you do it.

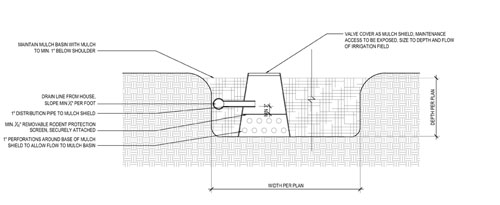

The system we are using is as simple as I could make it. I wanted all my greywater covered with mulch and hidden, but I need access to clean and service the system. This is the detail I used to show how the water gets into the mulch bed:

I included a rat barrier screen there because we have an issue with rats on this island, and I'm not crazy about them getting into the house through the greywater plumbing. They could still get through this, of course, but it would be a lot of work and it seems like I might notice the effort before it was successful. The rats were what kept me from doing a simple pipe with a drop over a mulch bed, because I couldn't figure out an easy way to keep rats out without having to clean a screen of yucky stuff regularly.

What I liked about this system was how simple it is. I already spend a fair amount of time doing maintenance on the irrigation system (which is getting a total overhaul during this big renovation so that should be fun), so I want the greywater system to be as simple as possible and with very straightforward maintenance. The law requires an owners manual for the system, but my aim is to make it so that manual is very, very short.

As we get to the actual installation portion of this, I'll add more detail. Keep your fingers crossed that we get through the building department review in a timely fashion.

posted by ayse on 09/07/15